When Caring Hurts

Insights for Helping Second Victims

Unanticipated clinical events occur within health care settings; some involve medical errors, while others may be the result of complications relating to the patient’s condition. Despite the best efforts of clinicians, hundreds of patients die each year. Clinicians closely involved in patient care are often deeply affected by these events, according to patient safety investigations (Scott & McCoig, 2016; Wu, 2000). Clinicians experiencing detrimental impacts from these clinical events are “second victims” (Dekker, 2013; Scott et al, 2009).

Nurses face many demands within clinically complex surroundings to practice the art and science of their chosen profession. Characteristically, nurses have strong emotional defenses to guide them through challenging shifts, allowing them to complete their assigned duties. However, when a patient under their care experiences an unanticipated clinical event—with or without an error—it can have lasting personal and professional effects. In the aftermath, nurses evaluate case events to help make sense of what transpired under their watch. Occasionally, these patient experiences can trouble even the most self-assured nurse, resulting in a vulnerable period in which she or he suffers as a second victim. We have learned that the second victim phenomenon can touch nurses working within any health care work environment across the continuum.

Historically, members of our health care workforce have suffered in silence from the career-related stressor of second victimization. Second victim prevalence can be as high as 43% of clinicians following unexpected clinical events (Seys et al., 2012). Feelings of shame, guilt, anger, fear, frustration and loss of confidence are just of a few of the many possible reactions experienced by an affected clinician (Sirriyeh, Lawton, Gardner, & Armitage, 2010; Scott et al., 2010). Many clinicians feel that they have failed the patient and begin to doubt their clinical competence, worrying about their ability to continue working in their chosen profession. It is not uncommon for these reactions to last days, weeks, months or even longer. These feelings do not easily resolve without external support from the individual clinician’s professional or personal social support systems. The purpose of this article is to provide insights into the second victim phenomenon and introduce ideas for leaders offering support to address the needs of health care’s second victims.

Second victim phenomenon

The term second victim was introduced by Albert Wu, MD, when he described the professional impact of a colleague’s medical error (2000). Intrigued by the frequent identification of suffering clinicians during post-event patient safety investigations, a University of Missouri Health Care research team began studying the lived experience of second victims. In 2009, this nurse-led research team introduced the now frequently cited definition for second victims as “health care providers involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, medical error and/or patient-related injury who are victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event” (Scott et al., 2009, p. 326).

Study participants easily recalled specific ”career jolting” incidents that resulted in a second victim experience (Scott et al., 2009), describing in scrupulous detail these clinical incidents, even years after the traumatizing event. It became evident that the second victim phenomenon posed serious threats to the clinician’s professional well-being.

Synthesized participant insights also exposed a predictable pattern of suffering and healing pathways (Scott et al., 2009). From these findings, a six-stage recovery trajectory describing stage characteristics and desired interventional strategies was designed. The sixth stage revealed a path of three potential endings: clinician thriving, surviving or dropping out. Refer to Table 1 for additional information on the second victim recovery trajectory.

The ability of the nurse to thrive in the aftermath of clinical events depends on the culture of the organization and its readily available resources for the clinician. It is vital that organizations provide the resources and environment that promote healing since failure to do so can cripple units or even service lines. Second victim responses have been accompanied by increased intent to leave the current role, increased absenteeism and staff burnout (Burlison, Quillivan, Scott, Johnson, & Hoffman, 2016). Yet despite a growing body of literature that unexpected clinical events, especially those relating to medical errors, can have ominous emotional consequences, many clinicians report not receiving adequate emotional support from their respective health care institutions (Edrees, Morlock, & Wu, 2017). Without appropriate social support from the work environment, some exceptional clinicians may experience long-term consequences of prolonged professional and personal suffering, or even worse, abandon the profession.

Caring for our own

Organizational awareness of the seriousness of the second victim phenomenon and an institutional response plan are significant steps in protecting clinicians. Basic elements of successful interventional program design include the presence of 1) a mature patient safety culture with guidelines to govern the handling of unanticipated clinical events, 2) a program to ensure providers are proactively aware of the second victim phenomenon and what can be expected from their organization and 3) an established social support intervention for individuals and teams of clinicians (Hall & Scott, 2012).

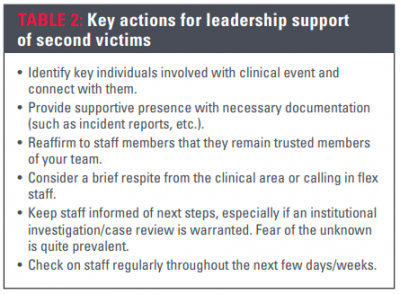

Nursing leaders play a pivotal role in clinician recovery. Leader presence after an event provides staff immediate emotional support. The leader can assist with determining if additional individual and/or group support is necessary. For additional insights into leadership support, refer to Table 2.

To support healthy caregiver recovery, many organizations have designed interventions with mental health professionals housed within their respective facilities or contracted with an agency/organization providing an employee assistance program or other mental health services.

Second victim phenomenon

The term second victim was introduced by Albert Wu, MD, when he described the professional impact of a colleague’s medical error (2000). Intrigued by the frequent identification of suffering clinicians during post-event patient safety investigations, a University of Missouri Health Care research team began studying the lived experience of second victims. In 2009, this nurse-led research team introduced the now frequently cited definition for second victims as “health care providers involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, medical error and/or patient-related injury who are victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event” (Scott et al., 2009, p. 326).

Study participants easily recalled specific ”career jolting” incidents that resulted in a second victim experience (Scott et al., 2009), describing in scrupulous detail these clinical incidents, even years after the traumatizing event. It became evident that the second victim phenomenon posed serious threats to the clinician’s professional well-being.

Synthesized participant insights also exposed a predictable pattern of suffering and healing pathways (Scott et al., 2009). From these findings, a six-stage recovery trajectory describing stage characteristics and desired interventional strategies was designed. The sixth stage revealed a path of three potential endings: clinician thriving, surviving or dropping out. Refer to Table 1 for additional information on the second victim recovery trajectory.

The ability of the nurse to thrive in the aftermath of clinical events depends on the culture of the organization and its readily available resources for the clinician. It is vital that organizations provide the resources and environment that promote healing since failure to do so can cripple units or even service lines. Second victim responses have been accompanied by increased intent to leave the current role, increased absenteeism and staff burnout (Burlison, Quillivan, Scott, Johnson, & Hoffman, 2016). Yet despite a growing body of literature that unexpected clinical events, especially those relating to medical errors, can have ominous emotional consequences, many clinicians report not receiving adequate emotional support from their respective health care institutions (Edrees, Morlock, & Wu, 2017). Without appropriate social support from the work environment, some exceptional clinicians may experience long-term consequences of prolonged professional and personal suffering, or even worse, abandon the profession.

Organizational awareness of the seriousness of the second victim phenomenon and an institutional response plan are significant steps in protecting clinicians. Basic elements of successful interventional program design include the presence of 1) a mature patient safety culture with guidelines to govern the handling of unanticipated clinical events, 2) a program to ensure providers are proactively aware of the second victim phenomenon and what can be expected from their organization and 3) an established social support intervention for individuals and teams of clinicians (Hall & Scott, 2012).

Nursing leaders play a pivotal role in clinician recovery. Leader presence after an event provides staff immediate emotional support. The leader can assist with determining if additional individual and/or group support is necessary. For additional insights into leadership support, refer to Table 2.

To support healthy caregiver recovery, many organizations have designed interventions with mental health professionals housed within their respective facilities or contracted with an agency/organization providing an employee assistance program or other mental health services.

Support in action—the forYOU Team

Based on research findings, University of Missouri Health Care implemented a second victim support infrastructure to provide emotional support for any clinician, staff, faculty, student or volunteer (Scott et al., 2010; Scott et. al., 2009). This evidence-based intervention to support health care’s second victims was initially piloted in 2007 and deployed across six hospitals and 52 ambulatory clinics in 2009. The forYOU Team, an interprofessional team consisting of volunteer nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, paramedics and other allied health professionals, offers immediate emotional and social support to affected clinicians.

Using an evidence-based three-tiered model of support, forYOU Team members address an individual’s unique needs, offering a menu of comprehensive emotional support ranging from instantaneous one-on-one conversations through professional counseling services (Scott et al., 2010). Each tier uses increasing institutional resources to address emotional needs of the suffering clinician. Interventions used by the forYOU Team are based on the understanding that each clinical event is a unique experience and each clinician may require a different intensity of support during their emotional recovery. While some clinicians may need only the resources available from one tier of support, others might need resources from all three tiers to help promote professional and personal recovery from the clinical event. Refer to Figure 1 for additional information on Scott’s Three-Tiered Model of Support.

Nurses working in clinically complex environments face the realization of unexpected and sometimes tragic patient outcomes. As a result, many staff suffer unsupported as they endure the acute occupational stress now known as the second victim phenomenon. It is important for nurse leaders to understand the second victim phenomenon to help put the experience into perspective and offer—and receive—the support required for healthy healing. Clinician support, regardless of practice location, should become a predictable part of a health care organization’s operational response to any unanticipated clinical event.

Reference

Burlison, J.D., Quillivan, R.R., Scott, S.D., Johnson, S. and Hoffman, J.M. (2016). The effects of the second victim phenomenon on work-related outcomes: Connecting caregiver distress to turnover intentions and absenteeism. Journal of Patient Safety, 13(2), 93-102. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000301

Dekker, S. (2013). Second victim: Error, guilt, trauma and resilience. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Edrees, H., Morlock, L., & Wu, A. (2017). Do hospitals support second victims? Collective insights from patient safety leaders in Maryland. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(9), 471-483. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.01.008

Hall, L.W., & Scott, S.D. (2012) The second victim of adverse health care events. Nursing Clinics of North America, 47(3), 383-393. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2012.05.008

Scott, S.D., Hirschinger, L.E., Cox, K.R., McCoig, M., Hahn-Cover, K., Epperly, K., Phillips, E., and Hall, L.W. (2010). Caring for our own: Deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 36(5), 233-240.

Scott, S.D. & McCoig, M. (2016). Care at the point of impact: Insights into the second-victim experience. Journal of Healthcare Risk Management, 35(4), 6-13.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L.E., Cox, K.R., McCoig, M.M., Brandt, J., & Hall, L.W. (2009). The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Journal of Quality and Safety in Health Care, 18(5), 325-330.

Seys, D., Scott, S., Wu, A., Van Gerven, E., Vleugels, A., Euwema, M., Panella, M., Conway, J., Sermeus, W., & Vanhaecht, K. (2013). Supporting involved health care professionals (second victims) following an adverse health event: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(5), 678-687. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.006

Sirriyeh, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Armitage, G. (2010). Coping with medical error: A systematic review of papers to assess the effects of involvement in medical errors on healthcare professionals’ psychological well-being. Journal of Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19(6), e43. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.035253

Wu, A. (2000). Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. British Medical Journal, 320, 726-727.

About the Authors

Susan D. Scott, PhD, RN, CPPS, FAAN

Director of professional nursing practice at University of Missouri Health Care, Columbia. Scott’s research was crucial in the design and deployment of a peer support network, the forYOU Team. She has partnered with agencies such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, American Hospital Association, The Joint Commission, Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the National Patient Safety Foundation to ensure that comprehensive second victim support interventions are accessible to health care organizations. She can be reached at susandonnellscott@aol.com.

Mary Beck, DNP, RN, NE-BC

Chief nursing officer of University of Missouri Health Care, and has a joint courtesy faculty appointment at the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, both in Columbia. She has been a strong advocate of the forYOU Team as part of University of Missouri Health Care’s healthy work environment initiative.